Structural Transformation: A Perspective from Chinese Growth Miracle

Generated by DALL·E

Generated by DALL·E“What drives growth in a country” has been an enduring topic in development accounting. Two things stand out in the minds of economists: for poor countries, K/Y is low and education is low. We will focus mainly on K/Y.

International Misallocation

One strand of the literature began with the Lucas paradox. In his 1990 paper, Lucas presented a paradox that capital does not flow from rich to poor countries even though the estimated MPK seems to be much higher in poor countries. Caselli and Feyrer (2007) made two adjustments to this calculation, and their results suggest that capital prices and MPKs are actually not very different between rich and poor countries.

Sectoral Misallocation and Agricultural Productivity Gap

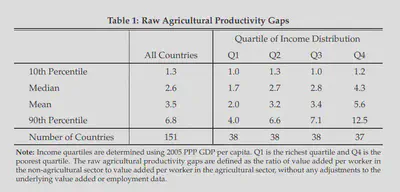

The other strand discusses the agricultural productivity gap (APG). The discussion centers on what plagues the development of the urban sector in poor countries, that is, a large share of the population remains in the agricultural sector when they could be more productive in the urban sector. This is true either when looking at national accounts data or when using micro-level data, as in Gollin-Lagakos-Waugh (2014).

In their estimates, the raw APG is 3.5 and the APG after all adjustments is 2.2. This deviates from 1, as we would expect in a frictionless setting - i.e., labor will go to whichever sector offers the higher return.

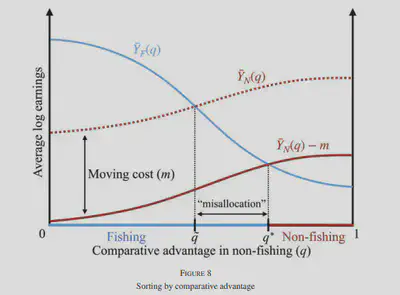

Follow-up literature suggests that there are frictions associated with workers moving from one sector to another. For example, education and skills1, social ties2, etc. And more studies have focused on the use of quasi-experimental evidence. For example, Nakamura-Sigurdsson-Steinsson (2021) shows that people who were induced to move from a high-income village by a volcanic eruption saw a large increase in income, but they were previously unwilling to do so because of “fixed” moving costs. (This is somewhat similar to the idea of price adjustment in a menu cost model, where firms are unwilling to adjust prices until the cost of a suboptimal price exceeds the fixed menu cost).

Some Facts about Chinese Growth

The classical view is that development is about reallocation out of agriculture into “modern” sectors3. As discussed above, this involves mobility between the agricultural and urban sectors, so a crucial consideration is how to overcome the moving costs that reduce sectoral mobility. One angle to look at the Chinese growth miracle is precisely this.

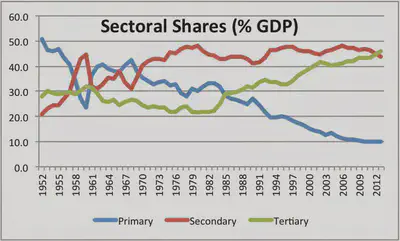

China has adopted this three-sector accounting model, where the primary sector is mostly agriculture, the secondary sector is heavy industry and manufacturing, and the tertiary sector is services. From the breakdown, we can see that the size of the agricultural sector declined significantly over time, while the industrial sector more or less reached its current level at the beginning of the opening period. Most of the growth in the post-liberalization period (after 1978) has been in services, which has gone hand in hand with the urbanization process.4

There are a number of ways to explain how China achieved high industrial growth in the 1950s and continued to do so in the 1960s. First, the data could be flawed and there could be huge mismeasurements. There is a whole body of literature discussing this, so I won’t go into it here. Second, if we believe that the data are telling the truth-that the structural transformation began before either the opening or the Household Responsibility System (HRS)5-then we might want to reconsider the economic impact of the central planning that took place in the 1950s and 1960s.

The Five-Year Plan

The Five-Year Plans are a series of social and economic development initiatives issued by the Chinese Communist Party since 1953 in the People’s Republic of China - they are both industrial policies and a manifestation of central planning.

After restoring its economic base, China, led by Chairman Mao Zedong and Premier Zhou Enlai, pursued socialist transformation. The First Five Year Plan, which ran from 1953 to 1957, was based on a Soviet model for economic and industrial expansion. It marked a shift in focus from peasants to urban industrial projects. The plan emphasized key tasks, including the construction of 694 large and medium-sized industrial projects. The Soviet Union aided in 156 projects, laying the primary foundations for China’s socialist industrialization.

Despite strains on agricultural production, the plan proved successful. “During this Plan period, China began developing a heavy-industrial base and brought its industrial production above what it had been prior to war. China also raised its agricultural production to above prewar levels, resulting primarily from gains in efficiency brought about by the reorganization and cooperation achieved through cooperative farming. Although urbanization had not been a specific goal of the plan’s focus on industrialization, industrialization also prompted extensive urban growth. By 1956, China had completed its socialist transformation of the domestic economy.”6

To summarize, Communist China achieved early-stage industrialization, especially in heavy industry7, in a short period of time. Meanwhile, the urban sector expanded significantly, both in terms of population and economic output. This shows that the rural-urban mobility barrier and sectoral misallocation were at least partially resolved.

A Two-Step Process

Based on the discussions above, I propose that the structural transformation from an agrarian economy into an industrial one that happened in China is a two-step process. The first step involves a relatively “authoritarian” approach to stimulate growth in the industrial sector and achieve early-stage industrialization (which requires both labor and technology). The second step centers around liberalizing markets, unleashing the power of the invisible hand.

While most of our focus has been on the second step, which brings about a good market structure, the first step should not be ignored. The goal of the first step is to overcome the “fixed costs” of achieving labor and capital mobility in the early stages of industrialization.

To do this, either one of the two needs to be satisfied:

- Endogenous: A boost in efficiency in the industrial sector to allow the industrial sector to overcome the initial fixed cost to move in both labor and capital.

- Exogenous: Plannings, laws or rulings by a state, wars or conflicts, colonization, etc. that makes capital and labor flow to the industrial sector (it’s not necessarily Pareto-efficient, but could be socially optimal in the long run)

China’s structural transformation in the 1950s and 60s seems to fall into the latter category. And England seems to be a mixture of both: on one hand, the Industrial Revolution was underway; on the other hand, the Parliamentary enclosure movement drove surplus peasant labor from their farms to the cities to become industrial workers. This is considered by some scholars to be the beginning of the emergence of capitalism. (I have yet to read more about this.)

Hence economists are often torn between two conflicting perspectives: on the one hand, good economic policy should produce favorable outcomes and therefore should prove also to be good politics; on the other hand, the implementation of good economic policy is often viewed as requiring “strong” and “autonomous” (not to say authoritarian) leadership.

–Dani Rodrik, Understanding Economic Policy Reform (1996)

Research Approach: Identification

The sources of variation that we can explore about Chinese growth are very limited. Causally-identified empirical work is unusually scarce, partly because of the lack of reliable, disaggregated official data, especially in the 1950s and 1960s.

However, one data source offers some promises. During the Cold War, the CIA’s CORONA and Keyhole-9 spy satellites collected thousands of high-resolution black-and-white daytime images of nearly the entire Earth’s land surface8. With remote sensing data, we can build a deep learning pipeline (such as with a CNN or YOLO) that identifies and distinguishes land used for agricultural versus industrial purposes. In addition, the Contemporary Chinese Village Gazetteer dataset digitized by the University of Pittsburgh is another fine-grained data source.

We can find variation in how different towns and villages pushed the First Five-Year Plan of industrialization (which places became the industrial centers) and explore how it contributed to the later-on economic growth.

Young (2013) and Hamory-Kleemans-Li-Miguel (2021) ↩︎

Munshi and Rosenzweig (2016) ↩︎

Rosenstein-Rodin (1943), Nurkse (1953), Lewis (1955), Rostow (1960) ↩︎

Note that the large increase in the secondary sector share could be a result of the decline in the primary sector during the Great Leap Forward, since the percentages must add up to 100%. But if the decline in the primary sector were the sole driver of this movement, we would also see a large increase in the tertiary sector, which is not really the case here. This suggests that at least some of this large increase in the secondary sector is real. ↩︎

See wikipedia. Also Lin (1988) is a highly-cited paper discussing HRS. ↩︎

The expansion of consumer goods manufacturing took place later during the opening up period. ↩︎

Following Kim and Ferguson (2023)’s approach. ↩︎