Barrier to Migration: Xin'anjiang Reservior

Xin’anjiang Reservior dam during construction

Xin’anjiang Reservior dam during constructionPoor countries have large and unproductive rural sectors. “One prominent feature of virtually every developing country is an enormous divide between rural and urban living standards, measured by income, consumption, or various nonmonetary aspects of life. As a result, much of the inequality within the developing world—home to about half of the planet’s nearly 8 billion people—is accounted for by the urban-rural gap.” (Lagakos, 2020) On average, Gollin, Lagakos, and Waugh (2014) find that value added per worker is 3.5 times higher in the nonagricultural sector than in agriculture, and poorer countries in particular appear to have a larger gap: the median gap is 4.3 in countries in the bottom quartile of the global income distribution, compared to 1.7 in the top quartile. More interestingly, now a large body of literature (e.g. Bryan et al. (2014), Chetty et al. (2016), Becker et al. (2020), Nakamura et al. (2021), Sarvimäki et al. (2022)) points out that those who migrate to the urban sector often enjoy higher incomes and better quality of life.

First, if farmers can earn more by moving to the urban sector, why don’t people move? Second, is labor misallocated and is there a potential for large gains from reallocating labor to the urban/modern sector? Finally, is rural-urban migration a key to economic growth?

Forced Migrations

One thing that a lot of people have looked at is forced migration (e.g. Nakamura et al. (2021), Sarvimäki et al. (2022)). Individuals are forced to relocate somewhere else due to wars or natural disasters. These are natural experiments that rule out the possibility of selection effects where higher productivity workers sort themselves into certain locations (i.e. cities), as opposed to locations having a direct positive causal effect on earnings.

Xin’anjiang Reservior

One series of forced migrations I would like to look at is the “dam displacement” in China beginning in the late 1950s. People were forced from their homes when their farmland was used to build hydroelectric dams. These forced migrations were large: between 1950 and 1999, an estimated 12.2 million people were displaced by hydroelectric projects, and 4.6 million people were displaced between 1950 and 1959 alone. A few key hydropower projects resulted in particularly large migrations: Three Gorges Dam displaced more than 600,000 people, Xin’anjiang Reservoir displaced nearly 300,000, etc. Most of the migrations were planned by local governments: for people in each village, there is a designated town and village they would migrate to.

As a starting example, I will focus on Xin’anjiang Reservior. This forced migration is very similar to Sarvimäki et al. (2022), where Finnish farmers were forced to migrate because part of their countries were ceded to the Soviet Union after WWII. In the Finnish case, most farmers were resettled into areas designated by the government that would “replicate” the original soil and weather condition for agricultural activities. Interestingly, compared to the locals in the resettlement areas, these newly moved-in farmers were more likely to migrate to cities afterwards and saw an increase in their income and children’s years of schooling. So the question is why didn’t they move before? What was the barrier? The authors attribute this to attachment to a place or “habit formation”: people accumulate location capital by living in a place.

Contrary to much of the literature on forced migration (including Sarvimäki et al. (2022)), the economic outcome of Xin’anjiang forced migration has not been positive. Many displaced families are still among the poorest in the country, and (I need to double check this number and its source) in 2008, more than 30% of the population living in poverty previously had to migrate due to hydroelectric projects. They did not move to opportunity; they moved to poverty.

Liquidity Constrainst

So what is different? I think liquidity constrainst is the key.

In my view, assets that make up the majority of rural household wealth (such as land, houses, and farms) tend to be illiquid and difficult to sell, imposing a liquidity constraint on the farmers and thus making the short-term costs of migration prohibitively high.

Rural farms, houses, and land are less liquid because the agricultural land market is thin and the demand for these assets is often local. On the other hand, in the literature that found a forced migration a positive shock often involve a handsome compensation: households received relief money for their houses destroyed by volcanic eruption in Nakamura et al. (2021); people were eligible for both government compensation and reconstruction loans (in very favorable terms) in Sarvimäki et al. (2022). In these cases, they essentially “cashed out” their illiquid rural real estate. This newly-found liquidity may offer an alternative explanation why the displaced farmers were more likely to migrate from rural to urban sector later.

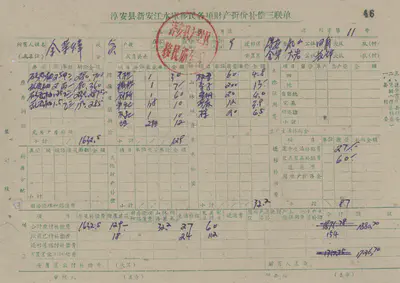

However, in the case of Xin’anjiang, later waves of resettlement coincided with the Great Leap Forward. Even though migrants were initially promised a reasonable rate of compensation, local officials sought to minimize costs, resulting in compensation that was far below the value of displaced assets. Thus the displacement might have exacerbated the liquidity constraints rather than alleviating it.

Exogenous Variation

To verify how compensation mechanisms interact with liquidity constraints and may aid migrations through alleviating liquidity constraints, I plan to conduct an in-depth study of a series of cases of forced migration, starting with Xin’anjiang Reservoir.

There are two unique features that I intend to explore as exogenous variations:

- Time variation: later waves of resettlement (low compensation) versus earlier waves (higher compensation)

- Geo-spatial variation: the reservoir was initially planned at a different location (before geological surveys deemed it unsuitable to build a dam); this creates another exogenous variation in the natural experiment.

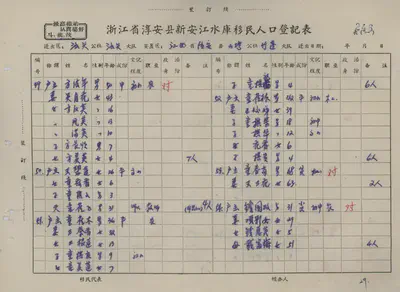

Xin’anjiang Reservior Archive

The available data is also fascinating. The Xin’anjiang Reservoir Migration Archive provides a comprehensive record of the entire process of relocating Chun’an residents. Organized by township, village, and household, the migration policy survey and processing registration forms contain detailed records for each migrant family, including population, resettlement locations, housing compensation, policy administration, and signatures and stamps of household heads. In particular, the lists, which cover 1,377 natural villages and nearly 290,000 migrants, clearly document each relocation. In 2006, the State Council issued documents on the post-transfer policy for migrants from large and medium-sized reservoirs and in the two years of 2006 and 2007 alone, the archives received more than 30,000 migrants who came to consult the records. The new policy provides additional compensation to migrants (600 RMB per year) and collects new data points on the economic outcomes of both migrants and their descendants.

By digitizing and examining this data, I hope to answer important questions about migration frictions. Specifically, I plan to compare the long-term outcomes of displaced households that received lower compensation (later waves) versus higher compensation (earlier waves) to shed light on how compensation relates to liquidity constraints and subsequently affect barriers to migration.

Other evidence

Other pieces of evidence might come from examining whether spatial mobility has increased when mass relocation took place for the construction of highways, railroads, infrastructure, or urban renewal. Difference in compensation may affect the ultimate economic outcome. In other cases, local government initiatives to revitalize rural real estate (farmlands are repurposed as tourist destinations; rural homes as “Airbnbs”—once hard-to-sell properties now high on brokers’ lists) may offer additional insights.

Going forward, I intend to expand my research by systematically studying the relationship between migration and economic growth in the context of historical and contemporary economic miracles around the world (e.g. the European rural-urban migration during the Industrial Revolution, the Great Migration of African Americans, China’s “Third Front” movement) I aim to disentangle the symbiotic and causal relationships between migration and economic growth.